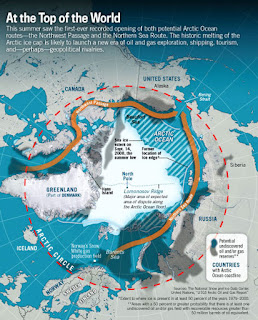

This year's opening marks the fourth time in five years that the Northeast Passage has opened, and commercial shipping companies are taking note. Two German ships recently are the first commercial voyage ever made through the Northeast Passage without the help of icebreakers. The Northeast Passage trims 4,500 miles off the 12,500-mile trip through the Suez Canal, yielding considerable savings in fuel. The voyage was not possible last year, because Russia had not yet worked out a permitting process. With Arctic sea ice expected to continue to decline in the coming decades, shipping traffic through the Northeast Passage will likely become commonplace most summers. The Northeast Passage has remained closed to navigation, except via assist by icebreakers, from 1553 to 2005. The results published in the American Association for the Advancement of Science suggest that prior to 2005, the last previous opening was the period 5,000 - 7,000 years ago, when the Earth's orbital variations brought more sunlight to the Arctic in summer than at present. It is possible we'll know better soon. A new technique that examines organic compounds left behind in Arctic sediments by diatoms that live in sea ice give hope that a detailed record of sea ice extent extending back to the end of the Ice Age 12,000 years ago may be possible (Belt et al., 2007). The researchers are studying sediments along the Northwest Passage in hopes of being able to determine when the Passage was last open.

The past decade was the warmest decade in the Arctic for the past 2,000 years, according to a study called "Recent Warming Reverses Long-Term Arctic Cooling" published in the journal Science. Four of the five warmest decades in the past 2,000 years occurred between 1950 - 2000, despite the fact that summertime solar radiation in the Arctic has been steadily declining for the past 2,000 years. Previous efforts to reconstruct past climate in the Arctic extended back only 400 years, so the new study--which used lake sediments, glacier ice cores, and tree rings to look at past climate back to the time of Christ, decade by decade-- is a major new milestone in our understanding of the Arctic climate. The researchers found that Arctic temperatures steadily declined between 1 A.D. and 1900 A.D., as would be expected due to a 26,000-year cycle in Earth's orbit that brought less summer sunshine to the North Pole. Earth is now about 620,000 miles (1 million km) farther from the Sun in the Arctic summer than it was 2000 years ago. However, temperatures in the Arctic began to rise around the year 1900, and are now 1.4°C (2.5°F) warmer than they should be, based on the amount of sunlight that is currently falling in the Arctic in summer. "If it hadn't been for the increase in human-produced greenhouse gases, summer temperatures in the Arctic should have cooled gradually over the last century,” According to Bette Otto-Bliesner, a co-author from the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Arctic sea ice suffered another summer of significant melting in 2009, with August ice extent the third lowest on record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. August ice extent was 19% below the 1979 - 2000 average, and only 2007 and 2008 saw more melting of Arctic sea ice. We've now had two straight years in the Arctic without a new record minimum in sea ice. However, this does not mean that the Arctic sea ice is recovering. The reduced melting in 2009 compared to 2007 and 2008 primarily resulted from a different atmospheric circulation pattern this summer. This pattern generated winds that transported ice toward the Siberian coast and discouraged export of ice out of the Arctic Ocean. The previous two summers, the prevailing wind pattern acted to transport more ice out of the Arctic through Fram Strait, along the east side of Greenland. At last December's meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the world's largest scientific conference on climate change, J.E. Kay of the National Center for Atmospheric Research showed that Arctic surface pressure in the summer of 2007 was the fourth highest since 1948, and cloud cover at Barrow, Alaska was the sixth lowest. This suggests that once every 10 - 20 years a "perfect storm" of weather conditions highly favorable for ice loss invades the Arctic. The last two times such conditions existed was 1977 and 1987, and it may be another ten or so years before weather conditions align properly to set a new record minimum.

As a result of this summer's melting, the Northeast Passage, a notoriously ice-choked sea route along the northern Russia, is now clear of ice and open for navigation. Satellite analyses by the University of Illinois Polar Research Group and the National Snow and Ice Data Center show that the last remaining ice blockage along the north coast of Russia melted in late August, allowing navigation from Europe to Alaska in ice-free waters. Mariners have been attempting to sail the Northeast Passage since 1553, and it wasn't until the record-breaking Arctic sea-ice melt year of 2005 that the Northeast Passage opened for ice-free navigation for the first time in recorded history. The fabled Northwest Passage through the Arctic waters of Canada has remained closed this summer, however. An atmospheric pressure pattern set up in late July that created winds that pushed old, thick ice into several of the channels of the Northwest Passage. Recent research by Stephen Howell at the University of Waterloo in Canada shows that whether the Northwest Passage clears depends less on how much melt occurs, and more on whether multi-year sea ice is pushed into the channels. Counter-intuitively, as the ice cover thins, ice may flow more easily into the channels, preventing the Northwest Passage from regularly opening in coming decades, if the prevailing winds set up to blow ice into the channels of the Passage. The Northwest Passage opened for the first time in recorded history in 2007, and again in 2008. Mariners have been attempting to find a route through the Northwest Passage since 1497.

WASHINGTON, Sept (Reuters) - Climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions pushed Arctic temperatures in the last decade to the highest levels in at least 2,000 years, reversing a natural cooling trend that should have lasted four more millennia.

Carbon dioxide and other gases generated by human activities overwhelmed a 21,000-year cycle linked to gradual changes in Earth's orbit around the Sun, an international team of researchers reported on Thursday in the journal Science.

"I think it really underscores how sensitive the Arctic is to climate change ... and it's really the place where you can see first what's happening to the (climate) system and how the rest of the Earth will or might follow," David Schneider, a co-author and a scientist with the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research said in a telephone interview.

The big cool-down started about 7,000 years ago, and Arctic temperatures bottomed out during the so-called "Little Ice Age" that lasted from the 16th to the mid-19th centuries, dove-tailing with the start of the Industrial Revolution.

This cooling trend was caused by a characteristic wobble in Earth's orbit that very gradually pushed the Arctic away from the Sun during the northern summer. Earth is now about 620,000 miles (1 million km) farther from the Sun in the Arctic summer than it was 2000 years ago, said Darrell Kaufmann of Northern Arizona University.

This cooling should have continued through the 20th and 21st centuries and beyond as the 21,000-year cycle played out. This latest research confirms that it hasn't.

"If it hadn't been for the increase in human-produced greenhouse gases, summer temperatures in the Arctic should have cooled gradually over the last century," Bette Otto-Bliesner, a co-author from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said in a statement.

What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay there, since it is among the world's biggest weather makers, sometimes called Earth's air-conditioner. As Arctic sea ice melts in summer, it exposes the darker-colored ocean water, which absorbs sunlight instead of reflecting it, accelerating the warming effect.

Arctic warming also affects land-based glaciers; if these melt, they would contribute to a global rise in sea levels.

Warming in this area could also thaw frozen ground called permafrost, sending methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

Climate scientists have long known that Earth wobbles in its orbit, which affects how much sunlight reaches the Arctic in the summer. This is the first time a large-scale study has tracked decade-by-decade changes in Arctic summer temperatures this far back in time.

To figure this out, researchers looked at natural archives of temperature -- tree rings, ice cores and lake sediments -- along with computer models, which tallied closely with the natural record.

Average summer temperatures in the Arctic have increased by about 3 degrees F (1.66 degrees C) from what they would have been had the long-term cooling trend remained intact.

The past decade was the warmest decade in the Arctic for the past 2,000 years, according to a study called "Recent Warming Reverses Long-Term Arctic Cooling" published in the journal Science. Four of the five warmest decades in the past 2,000 years occurred between 1950 - 2000, despite the fact that summertime solar radiation in the Arctic has been steadily declining for the past 2,000 years. Previous efforts to reconstruct past climate in the Arctic extended back only 400 years, so the new study--which used lake sediments, glacier ice cores, and tree rings to look at past climate back to the time of Christ, decade by decade-- is a major new milestone in our understanding of the Arctic climate. The researchers found that Arctic temperatures steadily declined between 1 A.D. and 1900 A.D., as would be expected due to a 26,000-year cycle in Earth's orbit that brought less summer sunshine to the North Pole. Earth is now about 620,000 miles (1 million km) farther from the Sun in the Arctic summer than it was 2000 years ago. However, temperatures in the Arctic began to rise around the year 1900, and are now 1.4°C (2.5°F) warmer than they should be, based on the amount of sunlight that is currently falling in the Arctic in summer. "If it hadn't been for the increase in human-produced greenhouse gases, summer temperatures in the Arctic should have cooled gradually over the last century,” According to Bette Otto-Bliesner, a co-author from the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Arctic sea ice suffered another summer of significant melting in 2009, with August ice extent the third lowest on record, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center. August ice extent was 19% below the 1979 - 2000 average, and only 2007 and 2008 saw more melting of Arctic sea ice. We've now had two straight years in the Arctic without a new record minimum in sea ice. However, this does not mean that the Arctic sea ice is recovering. The reduced melting in 2009 compared to 2007 and 2008 primarily resulted from a different atmospheric circulation pattern this summer. This pattern generated winds that transported ice toward the Siberian coast and discouraged export of ice out of the Arctic Ocean. The previous two summers, the prevailing wind pattern acted to transport more ice out of the Arctic through Fram Strait, along the east side of Greenland. At last December's meeting of the American Geophysical Union, the world's largest scientific conference on climate change, J.E. Kay of the National Center for Atmospheric Research showed that Arctic surface pressure in the summer of 2007 was the fourth highest since 1948, and cloud cover at Barrow, Alaska was the sixth lowest. This suggests that once every 10 - 20 years a "perfect storm" of weather conditions highly favorable for ice loss invades the Arctic. The last two times such conditions existed was 1977 and 1987, and it may be another ten or so years before weather conditions align properly to set a new record minimum.

As a result of this summer's melting, the Northeast Passage, a notoriously ice-choked sea route along the northern Russia, is now clear of ice and open for navigation. Satellite analyses by the University of Illinois Polar Research Group and the National Snow and Ice Data Center show that the last remaining ice blockage along the north coast of Russia melted in late August, allowing navigation from Europe to Alaska in ice-free waters. Mariners have been attempting to sail the Northeast Passage since 1553, and it wasn't until the record-breaking Arctic sea-ice melt year of 2005 that the Northeast Passage opened for ice-free navigation for the first time in recorded history. The fabled Northwest Passage through the Arctic waters of Canada has remained closed this summer, however. An atmospheric pressure pattern set up in late July that created winds that pushed old, thick ice into several of the channels of the Northwest Passage. Recent research by Stephen Howell at the University of Waterloo in Canada shows that whether the Northwest Passage clears depends less on how much melt occurs, and more on whether multi-year sea ice is pushed into the channels. Counter-intuitively, as the ice cover thins, ice may flow more easily into the channels, preventing the Northwest Passage from regularly opening in coming decades, if the prevailing winds set up to blow ice into the channels of the Passage. The Northwest Passage opened for the first time in recorded history in 2007, and again in 2008. Mariners have been attempting to find a route through the Northwest Passage since 1497.

WASHINGTON, Sept (Reuters) - Climate-warming greenhouse gas emissions pushed Arctic temperatures in the last decade to the highest levels in at least 2,000 years, reversing a natural cooling trend that should have lasted four more millennia.

Carbon dioxide and other gases generated by human activities overwhelmed a 21,000-year cycle linked to gradual changes in Earth's orbit around the Sun, an international team of researchers reported on Thursday in the journal Science.

"I think it really underscores how sensitive the Arctic is to climate change ... and it's really the place where you can see first what's happening to the (climate) system and how the rest of the Earth will or might follow," David Schneider, a co-author and a scientist with the U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research said in a telephone interview.

The big cool-down started about 7,000 years ago, and Arctic temperatures bottomed out during the so-called "Little Ice Age" that lasted from the 16th to the mid-19th centuries, dove-tailing with the start of the Industrial Revolution.

This cooling trend was caused by a characteristic wobble in Earth's orbit that very gradually pushed the Arctic away from the Sun during the northern summer. Earth is now about 620,000 miles (1 million km) farther from the Sun in the Arctic summer than it was 2000 years ago, said Darrell Kaufmann of Northern Arizona University.

This cooling should have continued through the 20th and 21st centuries and beyond as the 21,000-year cycle played out. This latest research confirms that it hasn't.

"If it hadn't been for the increase in human-produced greenhouse gases, summer temperatures in the Arctic should have cooled gradually over the last century," Bette Otto-Bliesner, a co-author from the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said in a statement.

What happens in the Arctic doesn't stay there, since it is among the world's biggest weather makers, sometimes called Earth's air-conditioner. As Arctic sea ice melts in summer, it exposes the darker-colored ocean water, which absorbs sunlight instead of reflecting it, accelerating the warming effect.

Arctic warming also affects land-based glaciers; if these melt, they would contribute to a global rise in sea levels.

Warming in this area could also thaw frozen ground called permafrost, sending methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere.

Climate scientists have long known that Earth wobbles in its orbit, which affects how much sunlight reaches the Arctic in the summer. This is the first time a large-scale study has tracked decade-by-decade changes in Arctic summer temperatures this far back in time.

To figure this out, researchers looked at natural archives of temperature -- tree rings, ice cores and lake sediments -- along with computer models, which tallied closely with the natural record.

Average summer temperatures in the Arctic have increased by about 3 degrees F (1.66 degrees C) from what they would have been had the long-term cooling trend remained intact.

0 comments:

Post a Comment